- Egypt Tour Magic

- Egypt Tour Packages

- Excursions in Egypt

- Cairo Tours and Excursions

- Hurghada Tours and Excursions

- Soma Bay Tours and Excursions

- Makadi Bay Tours and Excursions

- Sahl Hasheesh Tours and Excursions

- El Gouna Tours and Excursions

- Marsa Alam Tours and Excursions

- Port Ghalib Tours and Excursions

- El Quseir Tours and Excursions

- Dendera and Abydos Day Tours

- Aswan Tours and Excursions

- Luxor Tours and Excursions

- Alexandria Tours and Excursions

- Sharm El Sheikh Tours and Excursions

- Top Rated Tours in 2025

- Optional Excursions in Egypt

- Private Transfer

- Blogs About egypt

- Ancient Egypt

- What You Need To know Before Your First Trip To Egypt

- Best Places to Visit in Egypt 2025

- Top Attractions in Red Sea Resorts 2025

- Top 10 Tourist Activities in Egypt

- Top 30 Activities You Can’t Miss in Egypt

- The Guide to Guided Tours in Egypt

- Egypt’s Ancient and Modern History

- The Nile River

- The Deserts of Egypt

- Historical Sites in Egypt

- Cairo

- Alexandria

- Luxor

- Aswan

- The Red Sea

- Dendera Temple

- El Fayoum Oasis

- Bahariya Oasis

- Siwa Oasis

- Al Alamein

- Marsa Matruh

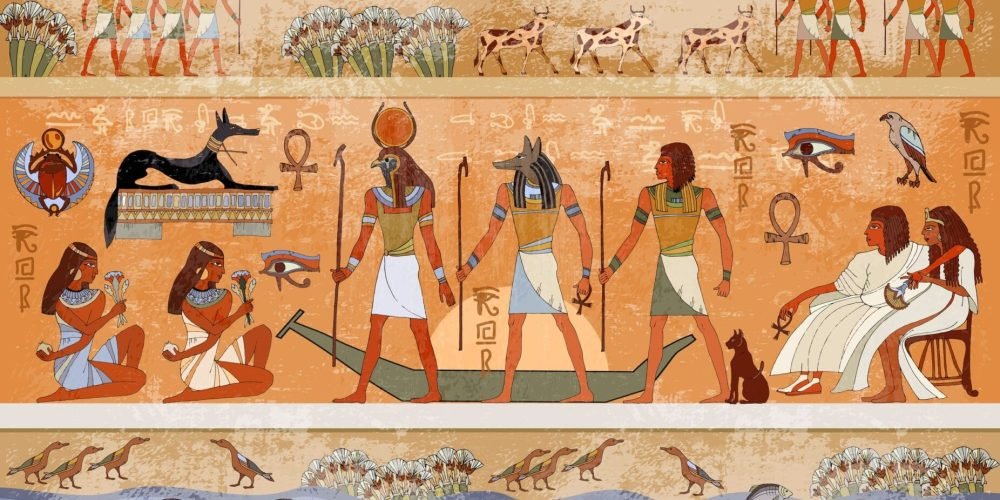

- Ancient Egyptian gods

- famous Egyptian dishes

- UNESCO World Heritage sites

- About Us

- Why Egypt Tour Magic

- Egypt Tour Magic

- Egypt Tour Packages

- Excursions in Egypt

- Cairo Tours and Excursions

- Hurghada Tours and Excursions

- Soma Bay Tours and Excursions

- Makadi Bay Tours and Excursions

- Sahl Hasheesh Tours and Excursions

- El Gouna Tours and Excursions

- Marsa Alam Tours and Excursions

- Port Ghalib Tours and Excursions

- El Quseir Tours and Excursions

- Dendera and Abydos Day Tours

- Aswan Tours and Excursions

- Luxor Tours and Excursions

- Alexandria Tours and Excursions

- Sharm El Sheikh Tours and Excursions

- Top Rated Tours in 2025

- Optional Excursions in Egypt

- Private Transfer

- Blogs About egypt

- Ancient Egypt

- What You Need To know Before Your First Trip To Egypt

- Best Places to Visit in Egypt 2025

- Top Attractions in Red Sea Resorts 2025

- Top 10 Tourist Activities in Egypt

- Top 30 Activities You Can’t Miss in Egypt

- The Guide to Guided Tours in Egypt

- Egypt’s Ancient and Modern History

- The Nile River

- The Deserts of Egypt

- Historical Sites in Egypt

- Cairo

- Alexandria

- Luxor

- Aswan

- The Red Sea

- Dendera Temple

- El Fayoum Oasis

- Bahariya Oasis

- Siwa Oasis

- Al Alamein

- Marsa Matruh

- Ancient Egyptian gods

- famous Egyptian dishes

- UNESCO World Heritage sites

- About Us

- Why Egypt Tour Magic

Ancient Egyptian Myths

1. The Egyptian Creation Myth

The creation myth in Ancient Egypt varies significantly across regions, but all versions agree that the universe originated from chaos or the “primordial waters” (Nun). In the Heliopolitan version, the myth revolves around the god Ra, who emerged from Nun and created the earth, the sun, and other gods. Ra’s creation marked the beginning of cosmic order and the establishment of the world as a place of balance and harmony. This version symbolizes the triumph of order over chaos and emphasizes Ra’s central role as the sun god and creator of all life.

In Thebes, the creation myth revolves around the god Amun, who is considered the creator emerging from the void, or the primordial waters. Amun, often depicted as a hidden or mysterious god, symbolizes the idea that the creator is beyond comprehension but is responsible for bringing forth the world and all its divine elements. As the creator of the universe, Amun embodies the concept of invisibility and mystery, associated with the forces that govern the world but are not directly seen.

Another widely recognized version comes from Hermopolis, where the god Atum is believed to have created himself from nothing, emerging from the primeval waters. Atum’s act of creation marks the beginning of the world. Atum’s name itself signifies the idea of being “complete” or “finished,” embodying the potential of everything in existence. Atum then produced other gods, beginning with his own children, Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), who later brought forth Geb (earth) and Nut (sky). This myth highlights the self-creation of the universe, where the beginning of all things originates from a single entity’s will and action.

These Egyptian creation myths share common themes such as cosmic order, self-creation, and the battle between order and chaos. They underscore the belief that the world was formed out of chaos by divine will and is sustained by the actions of the gods. The god Ra is central in several myths, symbolizing the sun and life-giving energy that dispels darkness and disorder. At the same time, Amun represents hidden power and the incomprehensible nature of the divine forces.

Furthermore, the concept of creation in Egyptian mythology is deeply tied to the cyclic nature of existence. The renewal of life and creation occurs not only at the start of the world but also during the daily cycle of the sun’s movement across the sky, where Ra’s journey through the underworld and back symbolizes the eternal return of light and life, ensuring the continuity of the universe.

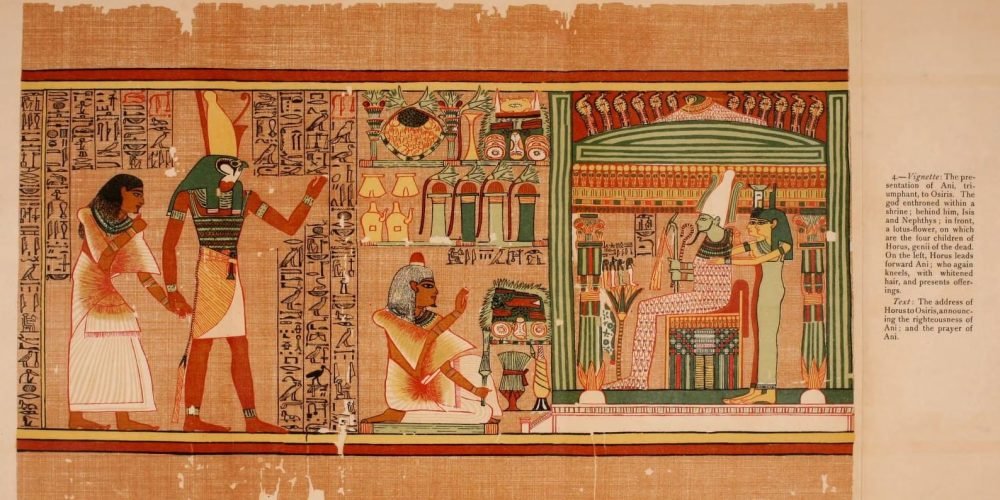

2. The Myth of Isis and Osiris

The myth of Isis and Osiris is one of the most significant and enduring stories in Egyptian mythology. It centers around Osiris, the god of life, death, and resurrection, who was betrayed and murdered by his jealous brother Set, the god of chaos and disorder, in a quest for power. Set trapped Osiris in a coffin and threw it into the Nile River, where it was carried away and eventually became lodged in a tree.

Upon learning of her husband’s death, Isis, the goddess of magic and motherhood, along with her sister Nephthys, embarked on a journey to find Osiris’s body. After a long search, they found him and, using her magical powers, Isis was able to briefly resurrect Osiris. During this time, she conceived their son Horus. However, Osiris could not stay in the world of the living and returned to the underworld to rule as the god of the afterlife.

As Horus grew up, he sought to avenge his father’s death and challenge Set for the throne. After a series of battles, Horus succeeded in defeating Set and restored balance and justice to the world, thus fulfilling his role as the protector of the living and the rightful heir of Osiris.

This myth encapsulates key themes in Egyptian belief: justice, resurrection, and the afterlife. Osiris, as the god of the dead, symbolizes the eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth, while his resurrection represents hope for life after death. The myth also highlights the divine order and the restoration of justice through Horus’s victory, with the gods working in harmony to maintain balance in the cosmos.

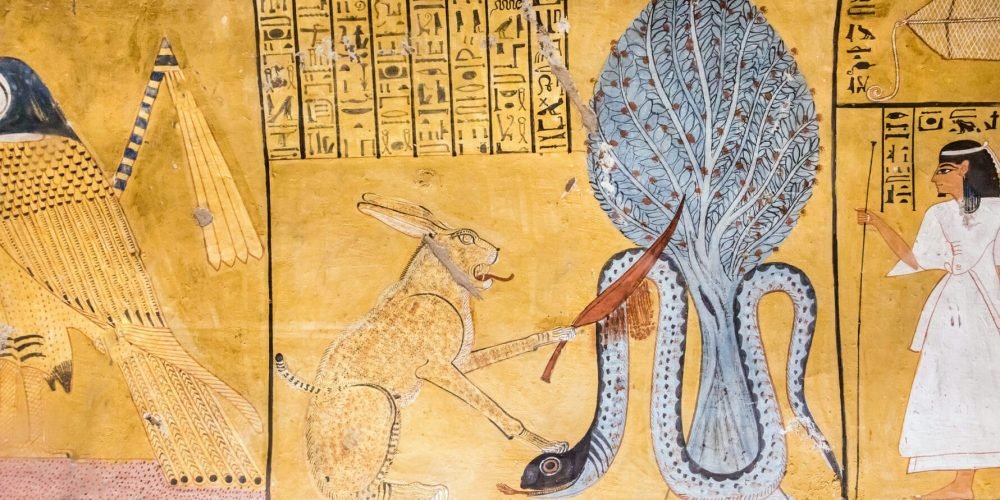

3. The Myth of Ra and Apophis

The myth of Ra and Apophis vividly illustrates the eternal struggle between order and chaos, a central theme in Egyptian mythology. Ra, the sun god, traveled across the sky each day in his solar barque, bringing light, warmth, and life to the world. His daily journey represented the triumph of order and the maintenance of balance in the universe. Ra was seen as the embodiment of the forces of cosmic order, ensuring that the world functioned according to divine law.

However, this cosmic order was constantly threatened by Apophis, a monstrous serpent god associated with chaos, darkness, and destruction. Every night, Apophis would attempt to prevent Ra’s passage through the underworld, aiming to stop the sun’s journey and plunge the world into eternal darkness. Apophis represented the forces of disarray and the dissolution of the cosmic harmony maintained by Ra.

To ensure that the sun would rise again each day, Ra had to confront Apophis in the underworld, often with the help of other gods such as Hathor, the goddess of love and joy, and Thoth, the god of wisdom and writing. In some versions of the myth, Ra’s defeat of Apophis required the collective power of various deities, as well as the strength and wisdom of Thoth to maintain cosmic balance. Ra’s victory over Apophis was symbolic of the triumph of light and order over darkness and chaos, ensuring the return of the sun and the restoration of harmony in the world.

This myth reflects the ancient Egyptian belief in the cyclic nature of the universe, where the daily battle between Ra and Apophis mirrored the eternal cycle of day and night. It also underscores the idea that order, symbolized by the sun, must constantly battle against chaos to sustain the world. The myth of Ra and Apophis was central to Egyptian cosmology and was often recited as part of religious rituals, as Egyptians believed that invoking these divine forces could help ensure the continued stability of the universe.

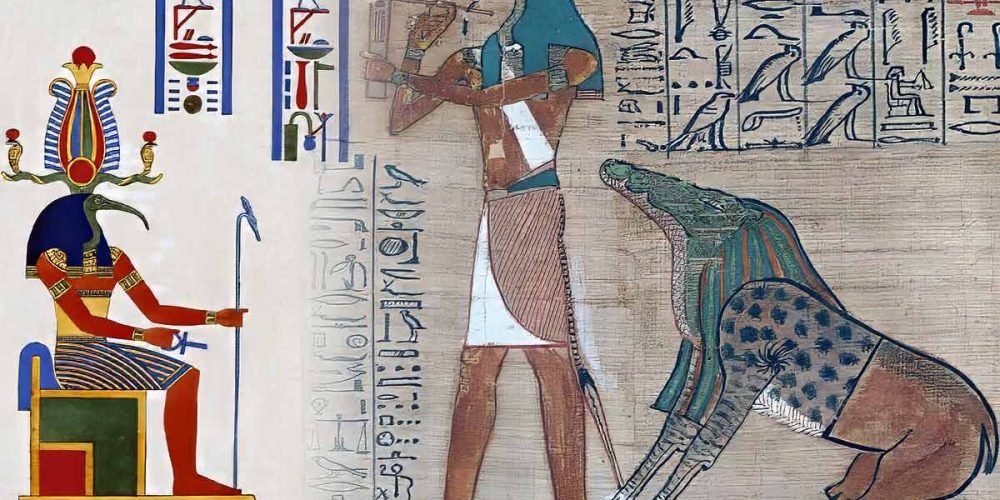

4. The Myth of Thoth

Thoth, the god of wisdom, writing, and knowledge, played an indispensable role in Ancient Egyptian mythology. He was regarded as the divine scribe, responsible for recording the actions and deeds of both gods and humans. As the scribe of the gods, Thoth was believed to possess vast wisdom and understanding, allowing him to keep accurate records of events in the cosmos. He was often depicted as a man with the head of an ibis or sometimes as a baboon, creatures sacred to him due to their association with wisdom and knowledge.

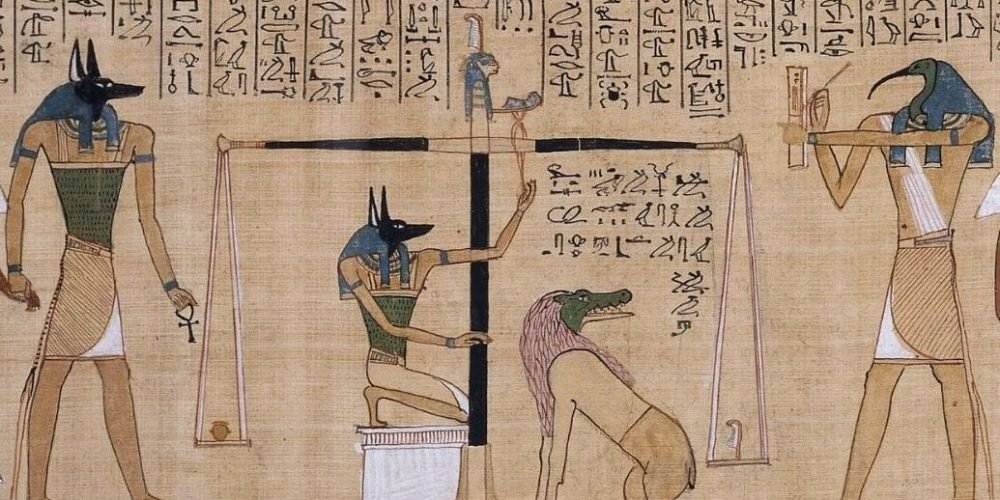

One of Thoth’s most important roles was his involvement in the Judgment of the Dead. This was a critical process in the Egyptian afterlife, where the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of Ma’at, symbolizing truth, justice, and order. Thoth was said to assist the goddess Ma’at during this judgment, ensuring that the process of weighing was conducted with complete fairness. If the heart of the deceased was lighter than the feather, it indicated a pure soul, worthy of entry into the Field of Reeds (paradise). If it was heavier, it suggested a life lived in dishonesty, and the soul would be devoured by the Ammit, a monster that represented destruction. Thoth recorded the results of this judgment, making him essential in the determination of whether the deceased would achieve eternal peace or face annihilation.

In addition to his role in the afterlife, Thoth was also considered the god who invented writing and language, including hieroglyphs. As a deity of knowledge, Thoth governed the arts of writing, mathematics, and medicine, contributing to Egypt’s intellectual and cultural achievements. His presence in Egyptian literature, science, and even magic highlights his significance in maintaining both divine and earthly order. Thoth was seen as a mediator, preserving balance in the universe by ensuring that wisdom, truth, and justice were upheld across both mortal and divine realms.

Thoth’s influence extended to the creation of the world itself, as he was sometimes associated with the beginning of time and the ordering of the cosmos. His wisdom was believed to be a vital force in maintaining the stability of the universe, and he was often consulted by other gods for his judgment on complex matters. Thoth was also the god of healing and magical incantations, making him an important figure for those seeking guidance in both life and death.

5. The Myth of Ma'at and the Importance of Justice

Ma’at was one of the most important deities in Ancient Egypt, representing truth, order, justice, and cosmic balance. She was the embodiment of the fundamental principles that governed not only the universe but also human behavior, societal laws, and the natural world. In Egyptian cosmology, Ma’at was essential for maintaining harmony and ensuring that everything in the world functioned in perfect balance. She was depicted as a woman with an ostrich feather on her head, symbolizing truth and justice, and was often shown holding the scales of justice or the feather itself.

Ma’at’s influence extended far beyond the divine realms and into the lives of humans. Egyptians believed that in order to achieve peace, prosperity, and a harmonious life, they had to live in accordance with her principles. These principles emphasized righteousness, honesty, fairness, and respect for the natural order. Ma’at’s laws governed everything from the proper conduct of kings to the behavior of individuals, ensuring that their actions contributed to the overall well-being of society and the universe. It was believed that anyone who lived a life in harmony with Ma’at would be rewarded with prosperity and favor from the gods, while those who violated her principles would face chaos and destruction.

Ma’at’s role was especially vital in the Judgment of the Dead. When a person died, their heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at in the underworld. If the heart was found to be as light as the feather, it indicated that the individual had lived a just and balanced life, and they would be granted entry into the Field of Reeds, an afterlife of peace and eternal happiness. However, if the heart was heavier, indicating a life of wrongdoing or dishonesty, it was devoured by Ammit, the soul-eating monster, and the individual was condemned to eternal oblivion. Thus, Ma’at’s role in the afterlife was critical for determining one’s fate based on the balance between good and evil actions.

The concept of Ma’at was also contrasted with Isfet, the force of chaos and disorder, which sought to disrupt the natural order and bring imbalance to the world. While Ma’at represented cosmic stability, righteousness, and truth, Isfet embodied disharmony, lies, and injustice. This constant struggle between Ma’at and Isfet represented the ongoing battle for balance in the universe, where the forces of order must continually fight to overcome the forces of chaos.

In Egyptian society, the pharaoh was seen as the earthly embodiment of Ma’at, tasked with ensuring that her principles were upheld throughout the land. The pharaoh’s role was not only as a political leader but also as the divine guardian of order, making sure that Ma’at was maintained in all aspects of life, from governance to agriculture to the cosmic cycles.

Ma’at’s teachings provided the foundation for moral and ethical conduct in ancient Egyptian society. Her principles encouraged people to live harmoniously with nature and each other, recognizing the importance of maintaining balance and order in all aspects of life.

6. The Myth of the Pharaohs and the Afterlife

According to Ancient Egyptian beliefs, the pharaohs did not die in the traditional sense, but rather began a transformative journey into the underworld after their death. This journey was a central aspect of Egyptian mythology and reflected the belief in resurrection and the continuity of life after death. The death of a pharaoh was seen not as an end, but as a transition to a new phase where the soul would undergo a judgment to determine its fate in the afterlife.

The Judgment of the Dead was a key element of this belief, where the pharaoh’s soul was judged by Osiris, the god of the afterlife, and was assisted by other deities such as Thoth, the god of wisdom, and Ma’at, the goddess of truth and cosmic order. In this judgment, the pharaoh’s heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at, which symbolized truth, justice, and order. The heart was considered the seat of a person’s spiritual essence, and it was believed to carry the record of a person’s deeds during their lifetime.

If the heart of the deceased was found to be lighter than the feather, this indicated that the pharaoh had lived a just and balanced life, in harmony with the principles of Ma’at. The soul was then deemed worthy of eternal life in the Field of Reeds, a paradise where the soul could live in peace, surrounded by abundance and tranquility, forever reunited with the gods. This afterlife was seen as a perfect world where the soul would experience eternal rest and happiness.

However, if the heart was heavier than the feather, this was a sign that the deceased had lived a life full of wrongdoing, dishonesty, or disobedience to divine laws. In such cases, the heart would be devoured by Ammit, a monstrous creature that was part crocodile, part lion, and part hippopotamus. The soul would be eternally consumed and denied entry into the afterlife, representing the final destruction of the individual.

This myth highlights the Egyptian belief in resurrection and the concept of immortality, where the pharaohs were considered divine beings capable of rising again in the afterlife. The belief in the Field of Reeds was closely tied to the Egyptian understanding of cosmic order, where living according to the principles of Ma’at ensured that one would find peace in the next world.

The journey of the pharaoh into the afterlife was also symbolized by the solar journey of the sun god Ra, who traveled through the underworld each night, only to rise again each morning. This mirrored the Egyptian belief in the continuous cycle of life, death, and rebirth, ensuring that the forces of chaos (Isfet) would never fully overcome the forces of order (Ma’at).

This concept of the pharaoh’s afterlife emphasized the importance of justice, truth, and balance in Egyptian society, and reflected the deep connection between the living, the divine, and the realm of the dead.

7. The Myth of the Goddess Hathor

Hathor was one of the most beloved and multifaceted deities in Ancient Egyptian mythology, embodying a wide range of qualities, including love, beauty, music, fertility, and motherhood. As the goddess of love and beauty, Hathor was often associated with the nurturing and protective aspects of life, particularly the well-being of women, mothers, and children. She was regarded as the protector of women during childbirth, ensuring safe deliveries and promoting fertility. This made her a central figure in the lives of women in ancient Egypt, with many seeking her blessings for fertility and health.

One of the most prominent myths involving Hathor is her role in restoring the strength of Ra, the sun god. According to the myth, Ra became weakened and lost his power due to the discontent of humanity, who had grown disrespectful of the gods. To punish them, Ra sent Hathor, who transformed into the fierce lioness goddess Sekhmet, a form associated with war and destruction. As Sekhmet, she rampaged across the earth, killing those who had angered Ra, and her actions were meant to restore the balance of power and maintain cosmic order. However, after her rampage, Hathor’s gentler nature prevailed. In some versions of the myth, she was tricked into drinking beer dyed red to resemble blood, causing her to become intoxicated and stop her destructive rampage. Hathor, in her true form, then returned to her role as a goddess of healing and restoration, bringing back peace and order.

Hathor was also deeply connected to joy, music, and celebrations. She was the goddess of music, dance, and festivities, and she was often depicted playing the sistrum, a musical instrument associated with her worship. Festivals in Hathor’s honor were filled with music, dancing, and singing, celebrating her attributes of joy, vitality, and life. Her association with happiness and celebration made her an essential deity for Egyptians seeking to bring positivity into their lives.

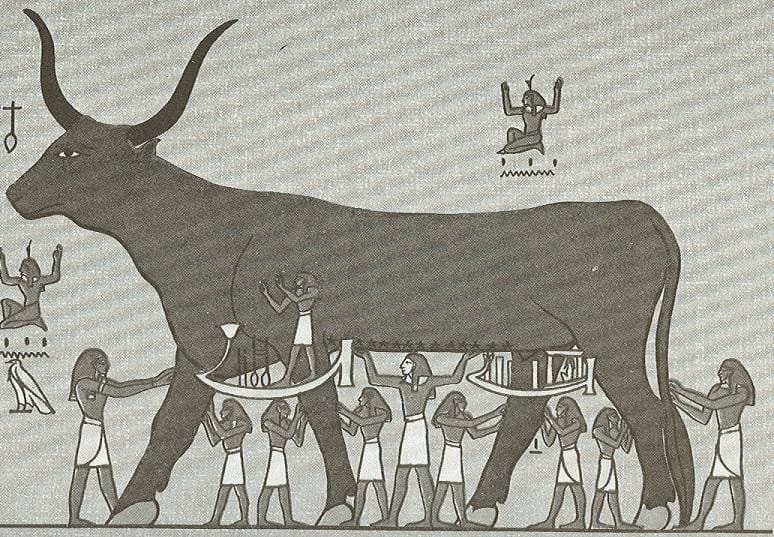

In addition to her nurturing and protective qualities, Hathor was also a sky goddess. She was depicted with a cow’s head or with a solar disk encircled by cow horns, symbolizing her connection to the heavens and her role in nurturing the world. In Egyptian cosmology, Hathor represented the maternal and protective aspects of the universe, ensuring that both the living and the dead were cared for and supported.

Hathor’s dual nature as both a nurturing mother and a fierce warrior in her Sekhmet form made her one of the most complex and revered deities in Egyptian religion. As a goddess of love, fertility, and music, she provided emotional and physical sustenance, while her role in the myth of Ra emphasized her capacity for power and strength when needed. Hathor’s image as a compassionate protector and joyful celebrator endeared her to the Egyptian people, ensuring that she remained one of the most worshipped and celebrated gods throughout the history of ancient Egypt.

8. The Myth of the Egyptian Afterlife (The Field of Reeds)

The Field of Reeds (also known as the Aaru) was the Ancient Egyptian version of paradise, a serene and idyllic realm where the righteous and virtuous souls could enjoy eternal peace and abundance. It represented the ultimate reward for those who lived their lives in accordance with the principles of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and cosmic balance. The Field of Reeds was considered the final destination for those who passed the Judgment of the Dead, a judgment presided over by Osiris, the god of the afterlife.

In Egyptian mythology, after a soul’s heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at in the Judgment of the Dead, those deemed worthy—who had led lives of righteousness, justice, and integrity—were granted passage into the Field of Reeds. This paradise was envisioned as a lush, fertile land filled with verdant fields, flowing rivers, and peaceful surroundings, echoing the beauty and fertility of the Egyptian Nile Valley. The souls who entered the Field of Reeds were believed to live in eternal harmony with nature, free from the suffering, illness, and death that characterized earthly life.

In this afterlife, souls would continue to lead a life that resembled the ideal life they had experienced on earth. They could enjoy food, drink, and comfort in the presence of loved ones and the gods. In the Field of Reeds, the soul was often depicted as living in a perfect version of the world, where all things were in balance and order. It was a place of abundance, where the soul could relax and enjoy the pleasures of life without fear of death or hardship.

The journey to the Field of Reeds was seen as an extension of life on earth, and the Egyptians believed that the soul’s ultimate goal was to reunite with the divine and achieve immortality. This afterlife was a reflection of the ancient Egyptians’ deep belief in rebirth and resurrection, and it served as a powerful motivator for individuals to live morally upright lives. Those who had passed the test of judgment and entered the Field of Reeds were considered to have attained a form of eternal existence, where they could experience peace, joy, and endless tranquility in a world without suffering.

The Field of Reeds was a deeply spiritual concept in ancient Egyptian religion, providing a hopeful vision of what awaited those who lived in accordance with divine order and truth. It represented not only the Egyptian belief in an afterlife but also their understanding of the importance of balance and harmony in both life and death.

9. The Myth of Set

Set, also known as Seth, was one of the most complex and controversial gods in Ancient Egyptian mythology. He was the god of chaos, disorder, storms, and violence, often associated with the destructive and unpredictable forces of nature. His character was multifaceted: on one hand, he was seen as a force of destruction and conflict, but on the other, he was also revered in certain circumstances, especially in his role as a protector against chaos and external threats.

One of the most famous and significant myths involving Set is the myth of Osiris. According to this myth, Set, jealous of his brother Osiris‘ popularity and power, sought to usurp the throne of Egypt. He tricked Osiris into entering a beautifully crafted chest, which he then sealed and cast into the Nile River, leading to Osiris’ death. This act of murder set off a chain of events that would fuel the eternal conflict between Set and Osiris’ son, Horus. The struggle between Set and Horus became a central theme in Egyptian mythology, symbolizing the battle between chaos (represented by Set) and order (represented by Horus). Horus eventually defeated Set, restoring balance and justice to the world. However, Set’s defeat was not complete; he was sometimes shown as continuing to resist and challenge the forces of order.

Set was also closely associated with the desert and storms. While the fertile land of Egypt was seen as the domain of gods like Osiris and Horus, Set ruled over the harsh, arid regions beyond the Nile Valley. He was believed to govern the destructive forces of sandstorms, floods, and other natural disasters that could bring about destruction and chaos. In this sense, Set symbolized the destructive, uncontrollable side of nature, the force that could overthrow the cosmic order established by the gods.

Despite his association with evil and disorder, Set was not entirely viewed as a purely malevolent figure. In some contexts, he was worshipped as a god who protected the Egyptians from external threats. He was especially revered in the military and warfare, as he was seen as a defender of Egypt against foreign invaders and a god who could help in times of conflict. Set’s image as a powerful and sometimes violent deity made him a suitable figure for those who needed strength and protection in battle. In this way, Set’s nature was dual: he was a destroyer of order, but also a protector against enemies that threatened Egypt’s stability.

Set’s complex nature as both a god of destruction and a protector reflects the Egyptians’ nuanced understanding of the forces of nature. He represented the uncontrollable and dangerous side of the world, but also served as a reminder that, in certain situations, the very forces that seemed destructive could also be harnessed to defend the cosmic order and maintain balance.

Set was frequently depicted in iconography as a creature with a curved snout, pointed ears, and a long tail, often referred to as the Set animal. This unique form was symbolic of his otherworldly and enigmatic nature, setting him apart from other gods in the Egyptian pantheon. Despite his violent actions and chaotic nature, Set played a crucial role in Egyptian mythology by embodying the concept that balance in the world requires both creation and destruction.

10 . The Myth of the Destruction of Mankind

The Myth of the Destruction of Mankind is a lesser-known but important story in Ancient Egyptian mythology that deals with the anger of Ra, the sun god, and the consequences it had for humanity. According to this myth, humanity became increasingly disobedient and disrespectful toward the gods, causing Ra to grow frustrated with the people he had created. As the king of the gods and the embodiment of the sun, Ra had created humans to serve the gods and maintain the cosmic order. However, over time, the humans began to defy the divine laws and engage in acts of rebellion.

In response to this defiance, Ra decided to punish humanity. He sent his daughter Hathor, in the form of the fierce lioness goddess Sekhmet, to destroy the offending humans. Sekhmet was a powerful and bloodthirsty goddess who unleashed chaos upon the earth, killing those who had angered the gods. The destruction was so widespread that it seemed like the end of humankind was imminent.

However, after a period of relentless destruction, Ra realized that the world would be left empty if the slaughter continued. He decided to stop Sekhmet’s rampage. In some versions of the myth, Ra used a clever trick to calm Sekhmet’s fury. He had beer mixed with red dye to resemble blood and placed it in front of her. Believing the liquid to be blood, Sekhmet drank it eagerly, becoming intoxicated and losing interest in the destruction. As a result, Ra saved humanity, but the myth reflects the balance between divine retribution and mercy, showcasing the importance of maintaining order and respect for the gods.

This myth highlights the Egyptians’ belief in the delicate balance between chaos and order in the world. It also reinforced the idea that while the gods were merciful, they would not hesitate to punish humanity if the cosmic order was disrupted.