The ancient Egyptian languages represent one of the oldest and most significant language families in human history. These languages, over thousands of years, evolved to serve the administrative, religious, and cultural needs of a vast and complex civilization. The development of the Egyptian language was intrinsically linked to the kingdom’s political structure, religious practices, and societal changes, and its legacy continues to influence modern understanding of the ancient world.

The Egyptian Language: Its Origins and Evolution

The Egyptian language belongs to the Afro-Asiatic language family, specifically within the Egyptian branch, and it evolved through several phases over millennia. These phases corresponded to major periods in ancient Egyptian history, including the Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, and New Kingdom. By analyzing the structure, grammar, and vocabulary of these languages, scholars have reconstructed much of the linguistic landscape of ancient Egypt.

Old Egyptian (c. 3300 BCE – 2200 BCE)

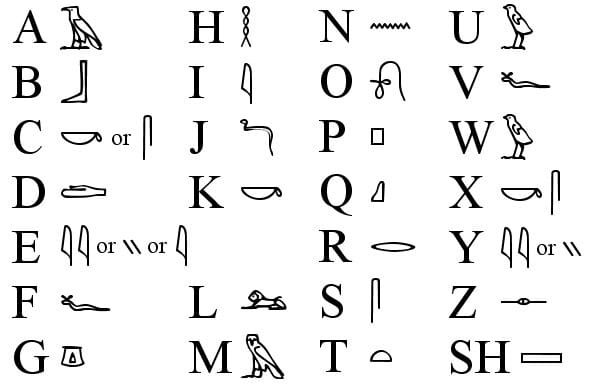

The earliest known form of the Egyptian language is Old Egyptian, which was used during the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE). This early form of the language was primarily used for monumental inscriptions, religious texts, and royal decrees. The language was written in hieroglyphs, a script consisting of pictorial symbols that represented both sounds (phonetic values) and meanings (ideograms). These symbols were used on temple walls, tombs, and royal monuments, serving as a primary medium for recording Egypt’s religious beliefs, historical events, and royal achievements.

The hieroglyphic script of Old Egyptian was highly complex and served as a medium of communication reserved for the elite, scribes, and priests. It was predominantly used in the context of religious rituals, monumental inscriptions, and royal decrees. This form of writing was closely tied to the religious and administrative aspects of life, where the pharaohs, considered divine rulers, used it to assert their power and document their relationship with the gods.

Middle Egyptian (c. 2000 BCE – 1350 BCE)

After the decline of the Old Kingdom, Middle Egyptian emerged as the dominant form of the language during the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000–1700 BCE). It is often referred to as the “classical” form of the Egyptian language, as it became the standard for literary, religious, and official texts during this period. Middle Egyptian remained the lingua franca for much of Egypt’s written tradition, even continuing to be used in religious texts and monuments long after its spoken form had evolved into later phases.

This period saw the introduction of more standardized forms of writing, such as the hieratic script, which was a cursive version of the hieroglyphic script. Hieratic was used by scribes for everyday writing on papyrus and other materials, such as legal documents, administrative texts, and literary works. The script allowed for faster writing and was particularly useful for recording historical and administrative data.

The Middle Egyptian language, in its written form, was used extensively in the composition of wisdom literature, religious hymns, and mythological texts, including the famous Pyramid Texts and the Coffin Texts, which describe the beliefs surrounding the afterlife and the gods. It is in this period that Egyptian writing began to flourish in terms of literature, poetry, and the codification of religious texts.

Late Egyptian (c. 1350 BCE – 700 BCE)

As Egypt entered the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE), the spoken language began to change, giving rise to Late Egyptian, which was the language of everyday life and government during this period. It marked a shift from the more formal and classical Middle Egyptian to a language that was more fluid and accessible. Late Egyptian was written in a cursive form known as demotic script, which was faster and more practical for everyday use, particularly for legal and commercial transactions.

Late Egyptian was used in a variety of contexts, including administrative, legal, and commercial documents, as well as in literary works. It reflected the growing interaction between Egyptians and foreign powers during the period of Egypt’s imperial expansion, particularly with the Hittites, Assyrians, and Persians. During the later stages of the New Kingdom, the hieratic script, derived from hieroglyphs, was used less in monumental contexts, while demotic became the dominant script for both official documents and daily communication.